Last Sunday, I awoke to the news of the racially motivated attack in Buffalo, NY. Sadly, the shooting that left 10 dead and was inspired by online extremism is not a new phenomenon. In fact, it follows a blueprint of similar attacks around the world of extremist online cultures. The shooter, Payton Gendon, left a manifesto (which he copied and pasted from similar manifestos left online) and cites Brenton Tarrent, the Christchurch mass murderer (2019), as his entry into online extremism and white supremacy. I’d recommend reading through our United Methodist Church’s General Committee on Religion and Race’s (GCORR) response to the Buffalo, New York tragedy and joining in the prayers offered.

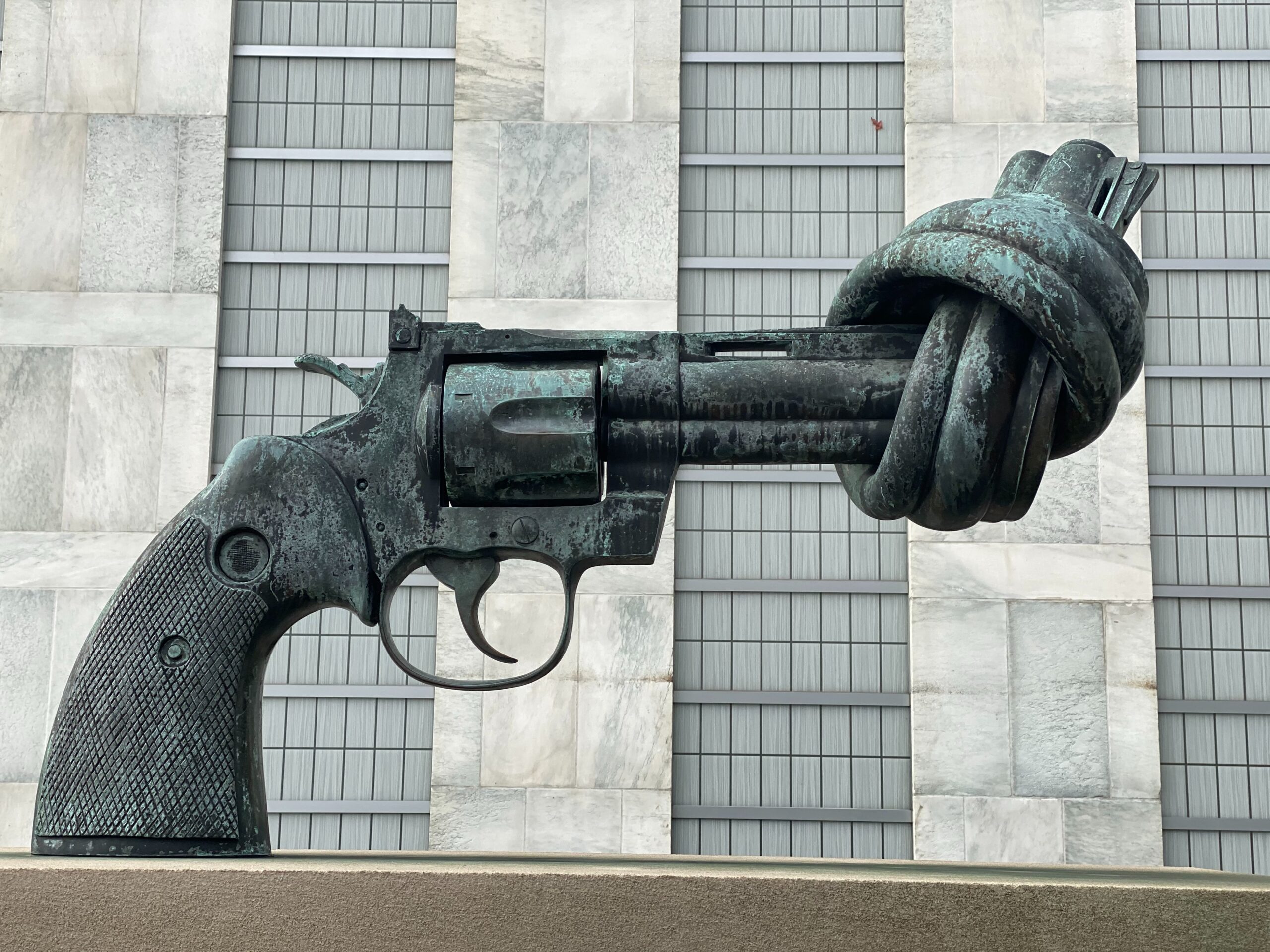

When the amount of mass shootings in a year are more than the actual days in a year, America must come to terms with the fact that this epidemic is not just ‘isolated individuals.’ It is an ideological contagion. And, this ideological contagion continues to spread. Even though we are just 19 weeks into 2022, America has already experienced 198 mass shootings which averages to around 10 shootings a week. If you take in other events related to gun violence, guns became the number one cause of death for U.S. children and teenagers in 2020–surpassing COVID-19, car crashes, and cancer. A contagion indeed. And, if there is one thing we have seen these past few years, we don’t handle contagions well as a society.

I have a few confessions and I’m just being transparent with you..

Confession 1: When I see the breaking news of another shooting, I find myself running through a swirling mixture of grief, shock, numbness, fear, overwhelmedness, anger, frustration, helplessness, and yes, wanting to ignore. I’ve skipped over articles and not engaged in these tragic events because of these feelings. Part of the reason I’ve delayed responding to this most recent event was I didn’t want to rush past by sending out a ‘thoughts and prayers’ response and move on to the next topic or story. Numbness or a sadistic sense of normality can emerge when these events feel so commonplace–something I wanted to avoid. Instead, I am choosing to sit with this mixture of feelings, acknowledge the wrongness, and pray on how to respond.

Which brings me to my next confession..

Confession 2: I want to help, but often feel at a loss at how to respond. Let’s face it, these conversations are extremely complex and involve so many dynamics both personal and systemic (racism, violence, gun access, culture, language, politics, power, money, and the list goes on). This is where that sense of being overwhelmed comes rushing in for me. The funny thing is, in conversations on these types of topics, I almost always hear phrases such as, “Well, we just need to do THIS thing.” or “It is the fault of THIS or THAT political leader.” Maybe you’ve heard those as well. There are plenty more statements that I can share that have a similar motif. Yet, these statements are not helpful in discovering ways forward. They create a cognitive dissonance by diluting ‘solutions’ to simple, highly reductive, definitive sounding responses. They, in effect, stop thought, reflection, and discernment through ignoring the complexity and enormity that is actually present in a conversation thereby shutting them down.

Maybe you’ve had similar experiences encountering these topics.

Something that helps me when encountering these tough issues and mixtures of feelings (especially of being overwhelmed) comes from the wisdom of Wendell Berry, one of my favorite poets and prophets. If I had to summarize Berry’s life-long and extensive work in a single sentence, it would be “a relentless search for health in the midst of disease”. To help connect these two conversations, I need to give you a brief review of his thinking concerning communities and health. And, if you find yourself relating to my own confessions concerning this topic, then I hope this helps you like it has me.

Berry’s understanding of ‘health’ within a society is framed within the concepts of finitude, humility, localness, boundedness, propriety of scale, and particularity. These aren’t words we use very often in our conversations or responses to these massive issues. In the opposite direction, buzzwords in our cultural discourse “such as global, comprehensive, progressive, efficient, profitable are often masks, ideas that seem polished and powerful on the surface yet refuse to give an account of full humanness, and so hide profound disease.” Why is that important? Because although we need an awareness of global issues, our responses always begin locally. I’ll come back to this a little later.

Now, what is striking about Berry’s ideas concerning health is that they are communal in nature. In a gathering of his writings, Berry writes (yes, this is a long quote):

“If we were lucky enough as children to be surrounded by grown-ups who loved us, then our sense of wholeness is not just the sense of completeness in ourselves but also is the sense of belonging to others and to our place; it is an unconscious awareness of community. It may be that this double sense of singular integrity and of communal belonging is our personal standard of health for as long as we live. Anyhow, we seem to know instinctively that health is not divided… I take literally the statement in the Gospel of John that God loves the world…. I believe that divine love, incarnate and indwelling in the world, summons the world always toward wholeness, which ultimately is reconciliation and atonement with God. And as the follower of Christ is only intelligible as such in the context of the larger body of Christ, so a healthy person is such only by reference to the community: “I believe that the community-in the fullest sense: a place and all its creatures-is the smallest unit of health and that to speak of the health of an isolated individual is a contradiction in terms… Most of the most important laws for the conduct of human life probably are religious in origin-laws such as these: Be merciful, be forgiving, love your neighbors, be hospitable to strangers, be kind to other creatures, take care of the helpless, love your enemies. We must, in short, love and care for one another and the other creatures. We are allowed to make no exceptions. Every person’s obligation toward the Creation is summed up in two words from Genesis 2:15: `Keep it… The inability to see things as they truly are always leads to a “selfishness, or even `enlightened self-interest,’ [that] cannot find a place to poke in its awl. One’s obligation to oneself cannot be isolated from one’s obligation to everything else. The whole thing is balanced on the verb to love.” “Wholeness, health, love-a set of notions emerges toward which we must bend our efforts within the flow of community. Only in dedication to the human face in each exchange can we enact a healthful love.”

Berry encourages us to accept our human boundaries (he uses the language of having a ‘Sympathetic Mind’) when it comes to fostering health. In essence, we are not all-knowing, all-powerful, or all-present beings, but finite and limited to our own experience within the context of a broken world–a world in the midst of redemption. Health, for Berry, is always connected to others/community. Health cannot be achieved in isolation and loneliness. Therefore, if we’re going to strive for health, we must “accept life in this world for what it is: mortal, partial, fallible, complexly dependent, entailing many responsibilities toward ourselves, our places, and our fellow beings… This is a countercultural notion in every sense; there is no path toward healing in modern culture-economic or political or religious-that does not lead back to the difficult labor of recognizing and honoring our finitude [and need for community].” Dr. William Cavanaugh also digs into this topic which I recommend as a follow-up since it will give a fuller picture of our limits in the midst of change: “Don’t Change the World”.

So what in the world does Berry have to do with what I confessed earlier about grappling with issues such as mass shootings, racism, and so on? For me, Berry recalls the fact that as followers of Christ, we need our church community–a community who is willing to practice the realities of Jesus’ kingdom together and engage these issues together through the discernment and guidance of God the Spirit. When we are isolated and individualized from others, we cannot see a path of healing and the possibility of change in our world seems impossible. By myself, the world can be pretty bleak. Yet, when we faithfully practice resurrection (the kingdom life) in and as a community, we experience a living example of what the world can and will become when Jesus redeems all things. We begin to see the most difficult issues around us in a new light, the light of resurrection, discerning ways forward in our localness together. As it says in scripture, “Truly I tell you, whatever you bind on earth will be bound in heaven, and whatever you loose on earth will be loosed in heaven. Again, truly I tell you that if two of you on earth agree about anything they ask for, it will be done for them by my Father in heaven. For where two or three gather in my name, there am I with them.”

Berry reminds me that although our responses to the issues in our world are anything but simple, it does simply start by seeking health with those closest to us–our neighbor. And, in God’s grace and goodness, together we discover those divine invitations to join in Jesus’ reconciliation of the world. Living with and experiencing God’s kingdom at work in our church reorients me from the numb overwhelmed feelings of the impossibility of global change to humble and concrete steps forward in my local community rooted in our hope in Jesus.

Now, take a moment and imagine local church communities all over the globe doing this very thing. That is when, for me, the possibility of transformation doesn’t seem so far-fetched.

“Life is better together.”